My personal perspective of the 2006 extreme mountain bike race across South Africa, “The Freedom Challenge”

Finding the soul of South Africa

Both water bottles on my bike were frozen solid, the tube to my hydration bag standing out like a piece of ‘bloudraad” (fencing wire) next to my shoulder. My hands were dead, and acting like a propeller was no longer having anyeffect. My speech was slurred, and I stopped thinking. I knew we were in trouble, but all I could do was rest my head on the handlebars and drift off to sleep.

“There’s a light! come on Ben, lets go!” said Cornell, fumbling with the gate catch. We both scrambled up the hill in the direction of the light. In the doorway of a small mud hut, the silhouette of a lady danced and swayed in the flickering glow of firelight coming from inside her hut. We could almost feel the warmth, comfort and safety of the fire when the door slammed shut, the bolt sliding home with a loud “thunk”. Dignity thrown aside, we stood at the door knocking, begging and pleading to be let in, but no amount of self humiliation could entice her to open her door to the two alien creatures she had seen running towards her that dark morning, skin alive and glowing (reflective tape) life support system (rucksacks) and a single evil white eye shining out the middle of our forehead (helmet LED)! Peeping trough a crack in the door, I could see her standing in the middle of the hut, hands clasped protectively in front of her trembling with fear.

With a creak of well-worn hinges, a door from the neighboring hut opened, and a lady, unaware of our presence, stepped out into the dark to empty a bucket into the frozen air. We needed no prompting and discarded all manners as we pushed past her and headed like a magnet for the small wood-burning stove in the middle of the kraal. With eyes closed, we crouched next to the stove and held on to the hot stovepipe as if worshiping a strange idol.

At some stage through the haze I felt a wooden crate gently pushed under me, and sank gratefully onto the bare planks. Again and again small pieces of wood were pushed into the tiny stove, while not a word was spoken.

Slowly, the warmth and comfort of the fire began to thaw my mind and I became conscious of pairs of wide bewildered eyes staring at us from all around the circular hut. Looking around, I saw that we were in the middle of a hut surrounded by an extended family of about fifteen people of all ages, huddled under blankets, hessian bags, newspaper, and coverings of all sorts of materials. After a time, we got up stiffly, mumbled our thanks, walked on stiff legs out of the hut and back onto the frozen steel of our bikes. We learned later that an escaped convict had recently terrorized the very same community.

It was 4 am.

Though not a single word was spoken during the incident in the hut, I will never forget the understanding, courage, compassion and generosity shown to us by that lady on that cold morning high in the mountains.

I had once again, experienced the “soul” of South Africa.

The Freedom Challenge is an extreme mountain bike race across South Africa, stretching from Pietermaritzburg in Kwa Zulu Natal to Stellenbosch in the Western Cape. The 2,300km route consists of gravel roads, two spoor dirt tracks, single cattle tracks an numerous portages where no tracks, paths or trails exist.

The route has been designed to pass through as many areas of natural beauty as possible, incorporating a number of nature reserves and conservation areas. The race is run during the middle of winter over some of the highest mountain ranges in South Africa where cold fronts and snow storms are a certainty at some stage of the route.

Why?

From the moment I first heard about the race and studied the details I knew that this was my race, a package of every experience gained through my life up to that point, the familiar stained and frayed jersey you love to wear around the campfire.

• It is unsupported, so once you start you are on your own in terms of decision making and basic survival.

• It is not a team race, although you are permitted to collaborate.

• It is nonstop, so although there are checkpoints at farm houses about every 100km or so, you choose if, when or where to stop, eat or sleep.

• The rules manual is one paragraph long, a paragraph longer than the safety regulations.

• No technical equipment such as GPS are permitted and the route is marked as a line on a series of orthophoto maps, low tech with high probability of getting lost on a daily basis.

• The outcome of the race is reliant on the integrity of each competitor to diligently follow the route and the rules, not catch a lift in the back of a pick up or take one of many possible short cuts.

• There is no prize money, the reward, a traditional Basutho initiation blanket, or a traditional whip with a maximum value of $30.

Bragging rights however, are pretty awesome.

Part 1

Day 1 - Pietermaritzberg to Allendale

105 km

1,980m climbing

11hrs cycling

Race tip #1: - Pack light:

It is amazing how generous some competitors became after the first day of the race, donating to the locals on a scale only exceeded by the National Red Cross Organization.

Start

This epic adventure started from the city hall in Pietermaritzburg as the church bell tolled 7am. Of the six of us who pedaled away on that Saturday morning, only four would cross the finish line in Paarl, some almost a month later.

Left to right; Greville Rudock, Geritt Pretorius, Andre Britz, Corness van der Westhuizen, Ben Swanepoel, Zolani Mtshali

The first day was a good introduction to the race, with some big climbs, a few short portages, river crossings and a jumble of forestry tracks. I planned to take it easy on the first day and only went as far as the first support station, 105 km from the start.

It was good to get going after so much anticipation, preparation and training, a bit like a scuba diver finally hitting the water and feeling the equipment and gear, so unwieldy on land, come into their own. It’s a tough first day but I felt relaxed and confident that I had a solid strategy to at least, break the record and didn’t heed the temptation to race after the guys running out front.

Meanwhile, on a very different strategy, Cornell Van Der Westhuysen, an architect from Johannesburg and an experienced long distanced cyclist blasted ahead to the first support station, stopping only for a quick bite before racing towards the second stop at Ntsikeni Nature Reserve another 90km away.

I enjoyed an excellent farm meal and settled in for an early night, fully aware that according to my careful planning and strategy, my personal race would begin in earnest at 1:30am, only a few hours away.

Day 2 - Allendale to Masakala

160 km

1,620m climbing

21hrs cycling

Race tip #2: - Obtain the handbook “Understanding Race Director language”:

For example:

• “It will take you guys 45 mins to do that section, max.” = It’s going to be a long cold night under the African skies.

• “Its do-able” = It can be done, as long as you are in a mode of transport that has an SAA sticker on the side, a day consisted of 48hrs, contour lines are measure in seconds, not meters, and all tracks marked on the map actually do exist on the ground.

• "Tomorrows cycle leg is really a non event" = Tomorrow you will be cycling more than double your normal distance, as we could not find a suitable support station in the area. You will probably blackout from sheer exhaustion, and not remember a single thing about the day.

• “Stettynskloof is going to kill you” = Stettynskloof is going to kill you. (see later)

Break Away

01:30 am saw me quietly dress and slip out into the crisp cold air, my secret betrayed as I almost ploughed headlong into a cow standing silently in the middle of the entrance road. It felt good to finally be alone, and for the first time this race felt real. Navigation proved a lot easier on this section than the previous year and before long I was on the winding forestry switchbacks leading up to the fist mountain portage to the Nsikeni Nature reserve.

On arrival at the lodge I was completely taken a back to find Cornell relaxing outside on the porch with no sign of preparations to move on. Over a quick lunch together, I heard how he had been caught by darkness the previous night while negotiating the portage, and had spent the night on the floor in a shepherds hut, waking during the night to the scurry of cockroaches covering the thin blankets given to him. Greeted to sharp stabbing pains in his knees that morning, the enormity of the race sunk in and he decided to abandon his original strategy and spend the day waiting for the rest of the competitors to arrive. was ready to move on, but after some discussion we realized we both had a very similar strategy in terms of actual distances and days, and decided to ride together at least for the next few days. In actual fact, we ended up riding together for the remainder of the race, the single best decision I made during the entire race.

For the rest of the day, we rode hard. The first few days of this race are incredibly difficult, mainly because your body is still adapting to the distances and sheer brutal effort that will soon become pare for the course. The only time I honestly thought about quitting was during those first two or three days.

I remember very little of that evening other than we struggled to find the village where our guest house was located. How we found it, what the rooms looked like, what we ate is still a mystery to me even though I can still easily recall every smell, taste and feeling of the remainder of the race.

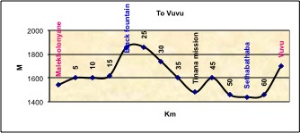

Day 3 - Masakala to Vuvu

125 km

1,200m climbing

18 hrs cycling

Race tip #3: - Nutrition Come into the race a few kilograms over your ideal weight.

During the race eat everything and anything you can get your hands on. Steal food from kind trusting country folk, your competitor’s rucksacks, and out of farmer’s lands alongside the road. Bang on doors in the middle of the Karoo demanding peanut butter and jam sandwiches.

At support stations, sneak into the lounge under the cover of darkness and remove (completely) all fruit from the creative display on the coffee table. Do not feel guilty. Very importantly, stop this behaviour immediately on completion of the race.

Heading for the berg.

Mentally and physically, this was the hardest day of the race for me (other than Stetynskloof of course). My motivation levels faltered at the mere thought of the physical effort and pain I knew would be needed to complete the daily route, and I started doubting if I really did have the mental and physical stamina to make it.

At one point I think Cornell realized how I was feeling, and he made me eat a couple of energy gels in spite of my weak protests. It’s just amazing how often a shortage of food (fuel) caused my motivation to plummet. Within a few minutes I was a new person. Food, or lack of decent nutrition, was a major issue for both of us on this day, and we suffered for it.

We rode hard the entire day, trying to put distance between ourselves and rest of the field at this early stage of the race when we knew everyone would be suffering and struggling to adapt to the demands of a race of this nature. We both paid some “toll fees” for our efforts, I managed to crash off the path and injure my knee which has never completely recovered, and Cornell went over the handlebars straining his wrist.

Navigation during this section of the route is notoriously difficult, and later that night, in coal black freezing conditions, we lost our way and had to negotiate a steep cliff, only to come up against a strongly flowing river. After searching the bank for a way over, we came to a reasonably flat stretch of water about 20m wide, and started wading across. Halfway across the frozen water, the firm sand bottom gave way and with shouts of alarm we were both swallowed up to our thighs in porridgy quicksand. We literally had to throw our bikes across to the bank and somehow managed to get across to the opposite bank without falling headlong into the icy water. I do not want to think of what would have happened had we soaked our bodies, clothes and kit in that water, with the air temperature already well below zero.

A few hours later, and utterly exhausted from climbing impossibly steep tracks, an “angel” in the form of a Catholic Priest from one of the mission stations drove up to us out of the blue with news that our designated support station was deserted. He had been searching for us for hours to give us this news. It was now close to midnight as he started banging on doors, eventually organizing for us to sleep in a shepherds hut. Blankets were quickly loaned from a neighbor and a small shop opened for us where we bought bread, bully beef, baked beans and yogurt.

I will never forget looking at a shelf of the shepherds one room hut, noticed that he had only one knife, one spoon and one plate, yet he was so generous to us. everything he had, he made available to us. Somehow, I got the spare bed, and Cornell the floor.

It was well after midnight when warm, safe, fed and dry, we fell asleep trying not to think of the 1 000m high portage over the Lehana pass that waited for us the following morning.

Day 4 - Vuvu to Rhodes

50 km

1,160m climbing

10 hrs cycling

Race tip #4: - Standard toolkit:

If the farmer’s toolkit consists of “bloudraad and tang”, then the freedom challenge toolkit must consist of “duck tape and a multi tool”. I used duck tape to create a new sidewall for my tyre; Amy used duck tape to repair a competitor’s knee joints.

Other uses include:

Waxing your legs (stick on, rip off),

Pain killer (Sniff the sticky side)

Competitive advantage. (Tape your competitor’s bike to his bedpost, and then slip out in the middle of the night)

Lehana Pass

The Lehana pass portage was one of the highlights of the route. A 1 000m elevation hike over the Maluti mountains following an infamous trail used by cattle thieves to bring their stolen goods on hoof into Lesotho from neighboring South Africa. The trail joins the gravel road at the top of Naudes neck, at 2 500m one of the higher mountain passes in South Africa. During the previous years race I had suffered as the weather closed in, driving temperatures down into the minus, reducing visibility to a few meters while we scratched around blindly looking for the trail in the growing darkness. It was only with the help of some shepherds crouching in a storm shelter that we finally reached the gravel road, and which point our troubles had only just begun.

This year however, everything was different, the weather was crisp but clear, the trail plain to see in the clear blue skies and my body finally in sync with my mind. We had finally become a team.

In warm sunshine, we pushed, pulled and carried out bikes up the ridge with all the Southern Drakensberg falling below us. Soon we were over the ridge and absolutely flying down Naude’s neck, where ice still clung to the rocks on the shoulder of the gravel road.

We reaching our support station at Rhodes in broad daylight and decided to celebrate the first big landmark of the race at stay put. It really was a well-deserved luxury and we bought a handful of sweets at a local shop to celebrate. We washed clothes, cleaned our bikes and soaked in a hot bath massaging our spirits for the next leg of this amazing race across South Africa.

Day 5 - Rhodes to Loutebron

125 km

1,080 m climbing

16 hrs cycling

Race tip #5: - What spares to take with:

Due to the high degree of technical advancement made on mountain bikes over the past few years, selecting the correct spares to take on a race of this nature has become a science in its own right. Based on my own valuable experience, I would recommend that the following hi-tech, ultra specialist items be included in your spares list:

• One bicycle tyre (Any old one will do)

• One standard bike cable (Price R7.00)

The chill before the storm

Now well ahead of the rest of the field and feeling stronger every day, we set out to make the most of our hard earned advantage. Climbing out of a warm bed in the middle of a winters night at altitude is not the easiest, but my “Just like heaven” ringtone helped.

Breakfast was a quiet affair, as we were the only guests stupid enough to be enjoying a hearty breakfast at 01:00 am. We later heard we had been accused of steeling the extra loaf of bread that went missing from the walk-in pantry at pretty much the same time as we were having breakfast.

At 02:00 under a charcoal canopy punctured with pinholes of a billion pulsating stars we set off, totally overwhelmed by the spectacular majesty of a night sky in its fullest splendor. What we failed to realize, was that the temperature was already well below freezing, (reported later as -9 degrees) and that as we descended into the long deep valley it would drop even further.

The wind chill factor of freewheeling downhill at over 30km per hour would cause us the pain and agony that left us crouched on a crate with hands glued to the wood stove in the middle of the shepherds hut. One moment disaster and the next, relief, such is the pain and pleasure, passion and dreary slog of racing the Freedom Ride. It is an emotional roller coaster ride in every way.

Another 110km of gravel road, two mountain portages, a shredded rear tire, and one day’s music rations, filled the passing of the sun. Cornell had raced ahead, and I rode alone for much of the day which was very enjoyable. I did wonder if he had actually broken away from me to race ahead but I didn’t mind, I had a pretty good race strategy, I was on schedule, feeling strong and had the advantage of knowing from the previous year what was still to come. found Cornell relaxing at the next support station and as soon as I had eaten, we took on the next portage over the mountains via a firebreak into the next valley just as darkness fell. We were keen to do the next portage in the dark anyway, but once again found ourselves at the receiving end of the mercy of “angel’s”. This time in the form of Japie Smith and his wife, who refused to allow us to proceed, insisted on taking us into their home. We had only come to them seeking local knowledge, but ended up giving ourselves over completely to the warm hospitality of rural South Africa.

Drugged on the contentment of full stomachs, clean clothes and warm fires we listened to Japie’s exploits on his trail bike, which he has adapted into a hill climber, complete with a trucks flywheel as a rear sprocket!

His favorite trick is to invite the city hill climbing trail bike clubs to his farm on weekends to test their high tech machines, and then, wearing shorts, long socks, vellies and a bush hat, “chug a lug” up near vertical mountain slopes and slabs of rock alongside the ”official” smoothed out hill climb as if on a Sunday paper run. He said he had some photos in a magazine to prove it, but I didn’t need to see to believe, not with Japie.

Blissful sleep.

Day 6 - Loutebron to Smuts Pass

120 km

880 m climbing

14 hrs cycling

Race tip #6: - Map Pouch:

Have some system whereby you can keep your daily route maps handy. You want to be able to check them while on the move.

Actually know how to read a map.

Storm

Cornell is an amazing navigator, probably something to do with well-developed spatial orientation due to his work as an architect. He always knew exactly where we were, except for today when during the early morning portage, we inadvertently descended the wrong valley. Although we didn’t loose much time as a result, it bothered him for the rest of the day.

It was also the day that the storm struck.

It started fairly mildly that morning, covering us with an icy mist as we neared the top of the porterage. Descending, we broke out the clouds, and it looked to be a cool cloudy day for our 115km trip to Smuts Pass just past Dordreght. We got all excited when we saw a few snowflakes drifting lazily down onto our clothes, laughing as we thought how we would report that we “cycled in a snowstorm!” Half an hour latter, the clouds released a carpet of thick silent snow, blanketing the landscape, our clothes and th road ahead. For the rest of the day, we cycled alternately through gently falling snow, icy wind, or freezing rain. I loved it, an amazing experience, silent, muffled movement.

Stopping at a Police station in the small settlement of Rossouw to confirm our navigation, we were summery detained without trial by the Station Commander, having to serve a sentence of fresh coffee, and a huge cooked lunch of venison and potato salad. We eventually received a pardon, and left with a suspended sentence of sandwiches, biltong, fruit and too many other goodies to mention, or to find the space to pack!

With evening, came the cold, not just an unpleasant cold, a life threatening numbness. Because of the minimum space and weight we could afford, we only had cold weather clothes to keep us warm while we cycled hard. The moment we stopped, the cold became desperate. Stopping for more than a few minutes was not an option. Riding off into that dark cold night with not a single light or landmark was a matter of faith, not confidence, and I remember making a mental note of the position of a hay stack I saw flashing past my headlight, thinking that we could always take shelter among the bales. At about 10:00 pm, we finally saw a light in the distance and after fumbling around in the dark being misdirected by a well meaning shepard arrived at the support station, an old colonial styled lodge.

Our experience here, after the extreme cold and uncertainty of the days ride, can only be described as fantasy. I will never forget the incredible sense of inner warmth and peace we felt, sitting on the floor in front of the huge log fire, a plate of hot food in my lap. Around me, the comforting “buzz” of a family quietly busy with the normal things that normal people do in a million normal homes around the world.

Although late, we somehow found the energy to service and wash our bikes, wash clothes and prepare for an early morning start. Sleep beneath a mountain of soft down came easy and sweet.